What will a vacuum cleaner look like five years into the future? Will it even exist on the market in its current form? Will machine learning (ML) turn today's vacuum cleaning robots into significantly more versatile and 'intelligent' house-keeping machines? No one knows for sure, but I bet folks at Phillips, iRobot, Dyson, and similar companies are busy figuring out what (or who) will clean our homes several years down the road. They don't have to guess blindly, as various design methodologies help them envision future developments.

Design fiction is a speculative design discipline that helps designers forecast future contexts and the impacts of emerging trends. These trends don't feature only technological advancements. They also involve shifts in social, political, economic, legal, environmental, and other domains. The goal of this practice is not to produce market-ready designs but to facilitate exploration and discussion about future innovation strategies.

Design fiction is rooted in science fiction and has numerous applications in arts, academia, and research. More recently, it has been finding its footing in the commercial realm. For companies to keep up with the competitors, it's not enough to innovate for today's customers. They must understand how their users and markets will change three, five, or ten years into the future. This need has sparked the emergence of design fiction consultancies worldwide, such as the Near Future Laboratory, with outlets in multiple countries. Such consultancies help clients envision future contexts and help them engage in constructive discussions about the future direction of their innovation endeavours.

Design fiction involves ample research to understand user needs and uncover trends with significant potential to influence the future. This phase is usually followed by forecasting, attempting to envision how these trends will shape specific future outcomes and events. A variety of forecasting models is used for this purpose. One of the most notable ones is the Futures Cone diagram, also known as The Voroscope, named after its creator, physicist and futurist Joseph Voros. (Voros, 2017) The model allows designers to map outcomes/events along a future-projected timeline and within numerous probability-based categories, from probable to preposterous.

However, research data and forecasting models are often insufficient to spark discussions. Therefore, designers rely on storytelling to create a clear vision of future contexts and engage participants. Two notable tools/outcomes are used for this purpose: scenarios and diegetic prototypes. The design fiction scenarios can be much like short Sci-Fi scripts or stories, often following a standard 3-act structure where the target user takes the role of a protagonist battling obstacles.

A prototype is a more or less refined representation of a future product. Prototypes are a standard feature in design thinking/user experience design to test design functionalities on users before releasing the full-fledged solutions onto the market. However, diegetic prototypes serve a different purpose. They are much like the props from science fiction movies to help tell the story and engage the audience. They don't necessarily have to be futuristic physical or digital products. For example, when collaborating with Ikea, rather than designing futuristic furniture, accessories, and appliances, the Near Future Laboratory designed a fictional IKEA catalogue presenting people living and interacting in the Internet of Things (IoT) augmented living rooms, kitchens, and bedrooms.

Design fiction integrates various approaches and methodologies, not just from the design field. However, it primarily incorporates design thinking and systems thinking. Design thinking is a user-centred approach where designers aim to create design outcomes tailored to the needs and preferences of their target users. This approach involves significant research, experimentation, and testing before settling on the final design outcome. For example, designers and developers creating a new digital application will heavily test its look and functionality before releasing it onto the market.

Systems thinking is a more holistic approach, investigating broader real-world contexts, interactions, and relationships. With systems thinking, designers do not consider only the needs of their target users when developing a new product or service but explore its wider social, ethical, and environmental impact. For example, AI image generators, such as Midjourney, may perfectly meet the needs of their target audiences by generating captivating shots quickly and effortlessly. However, the corporations behind these image generators did not consider the ethics of harvesting millions of images from professional artists and photographers without consent and compensation to train their machine-learning models.

One of the vital roles of design fiction and systems thinking involves reducing the negative environmental impact of consumer products through sustainable design, as embodied in the circular economy concept. As opposed to linear economy, which, by design, harvests resources from the ground, turns them into often short-lived consumer products, and discards them after use, its circular counterpart aims to minimise the extraction of materials and their accumulation in landfills and plastic continents.

Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF), headed by and named after a world-renowned long-distance sailor, is spearheading the effort to promote and popularise circular economy. As defined by the EMF (cited in Weetman, 2020), the circular economy aims to design out waste and pollution by selecting environmentally friendly materials and processes and keep products and materials in use as long as possible to prevent them from accumulating as waste. It also strives to regenerate natural systems by returning the nourishing ingredients captured in our products back to the soil. (Weetman, 2020, p. 25)

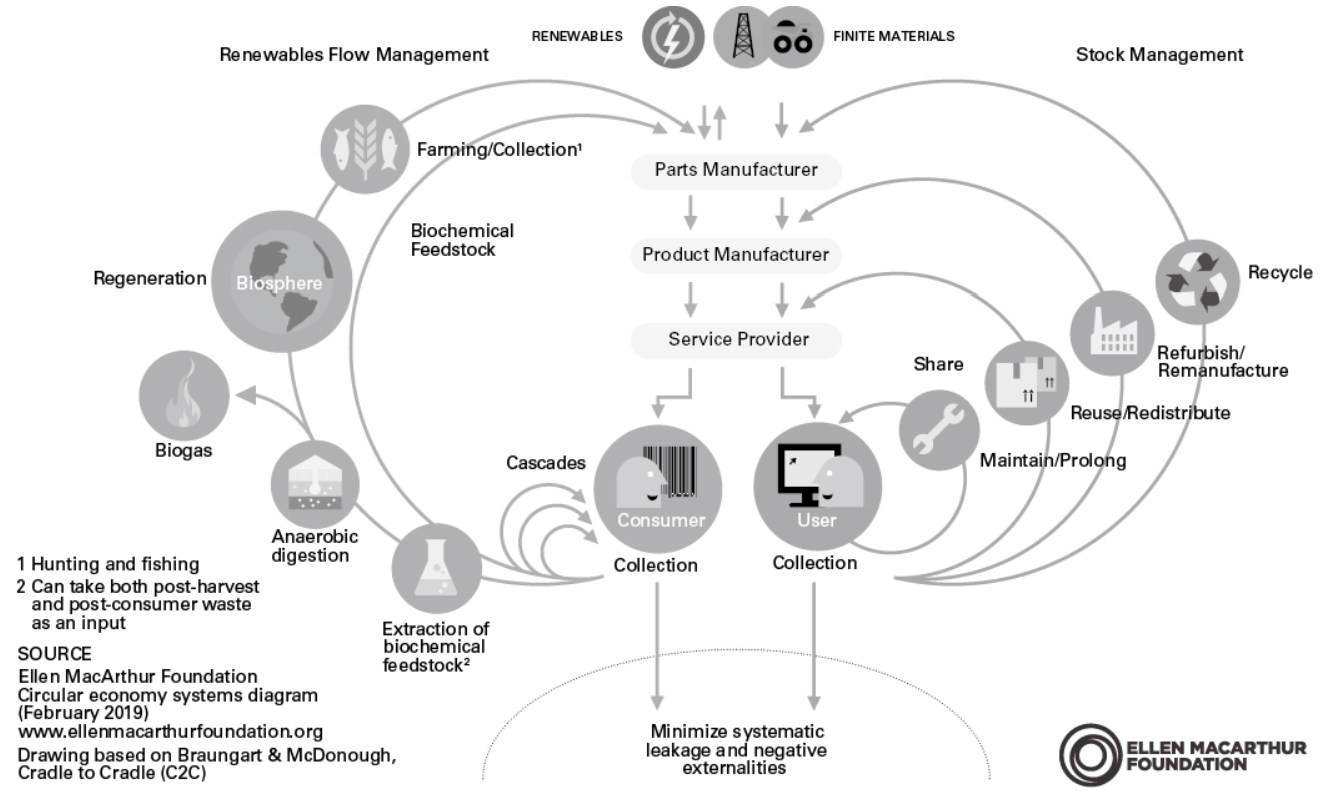

Figure 1. Circular Economy Systems Diagram (Butterfly Diagram) by Ellen MacArthur Foundation from Circular Economy Handbook, p. 25

The EMF's philosophy is embodied in the butterfly diagram, named after its shape resembling a butterfly. It envisions various circular flows of natural renewables (e.g. wood) and human-made finite materials, such as plastic or metal, to optimise their impact as they circulate through our socio-economic and environmental systems. Such circular flows involve methods such as cascades, sharing, reuse, maintenance, repair, refurbishing, remanufacturing, recycling, and others.

Figure 2. Interactive Container for Storing and Analysing Food by K. Ilia

At Arden's CMI-accredited MA Visual Communication Design (Management) programme, design fiction and sustainable design are the focus of the Emerging Communication Design module. Within the module, the students carry out research to identify contemporary trends and incorporate them into forecasting models, such as the futures cone, to envision the outcomes and scenarios shaping our collective future. Such scenarios often deal with the impacts of pollution and climate change and serve as the foundation for designing respective diegetic prototypes of future products.

Figure 3. Screen Designs for the Food Analysis Application by K. Ilia

The students incorporate butterfly diagram circular flows into their designs. However, these solutions often go beyond integrating environmentally friendly materials. For example, student Konstantina Ilia designed a food container from glass and bamboo, primarily intended for storing leftovers. However, the container's real impact stems from integrating nanotechnology, machine learning, and the Internet of Things (IoT). With these technologies and their communication with a smartphone app, the container would analyse the food stored inside, recognise harmful ingredients, such as additives and pesticides, and alert the user when the stored food may be approaching spoilage. Such functionality would turn an ordinary food container into a tool for building healthy eating habits, consuming environmentally friendly food products, and reducing food waste.

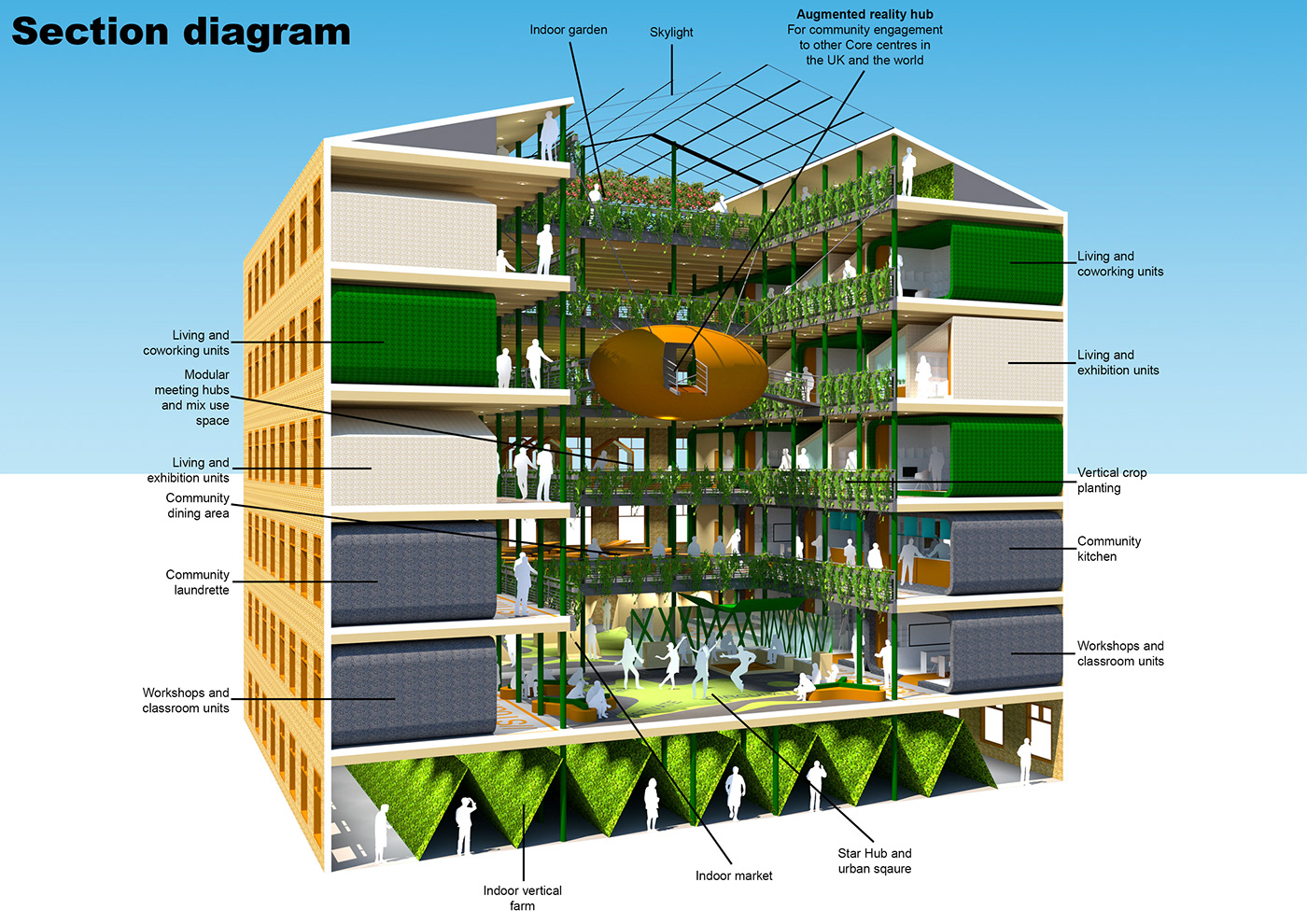

Figure 4. Section Diagram of the Repurposed Modularly Constructed Mill (Core) by Z. Lau from Behance.net

While sustainable/circular design is the focus of the Emerging Communication Design module, such practices are integrated into various practice-based modules on the BA and MA levels. In the Industry Competition Briefs module, a part of the BA (Hons) Graphic Design programme, the students are asked to create design solutions that address the ongoing design competitions, often emphasising ecology and sustainability. As a solution for the Planet Generation challenge as a part of the Royal Society of Arts Student Design Awards 2023, student Zoen Lau has taken the task of reinventing a derelict industrial mill in Halifax, United Kingdom. Applying a range of sustainable design practices, the student has envisioned a self-sufficient residential communicating incorporating a sustainable lifestyle, circular economy, and community engagement and collaboration. This design has earned Zoen a place in the 2022-23 RSA Student Design Awards shortlist and the 2023 Creative Conscience Silver Award. Congratulations Zoen!

With the technological landscape changing rapidly, we don't need the futures cone to realise the potential of design fiction and circular design in making our production and consumption practices more sustainable.

References

Voros, J. (2017). The Futures Cone, use and history. [online] The Voroscope. Available from: https://thevoroscope.com/2017/02/24/the-futures-cone-use-and-history/.

Weetman, C. (2020) Circular Economy Handbook. [online] 2nd ed. London, Kogan Page.

Guest Posts